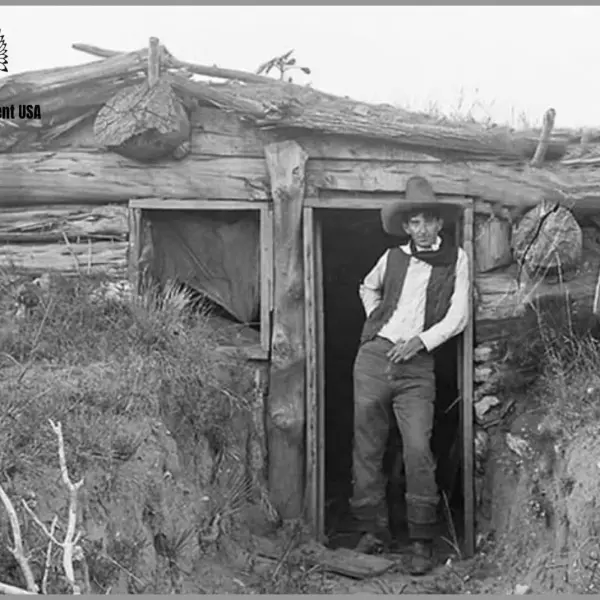

Judge Roy Bean’s notary office

Judge Roy Bean’s Notary Office: The Law West of the Pecos

Phantly Roy Bean Jr. (c. 1825–March 16, 1903), a colorful figure of the American Old West, is best known as the self-proclaimed "Law West of the Pecos." Operating out of his saloon, the Jersey Lilly, in Langtry, Texas, Bean served as a Justice of the Peace and notary public, dispensing a unique brand of frontier justice in the desolate Chihuahuan Desert along the Rio Grande. His notary office, intertwined with his saloon and courtroom, became legendary for its eccentric rulings and Bean's larger-than-life persona.

The Origins of Bean's Notary Office

In 1882, Roy Bean arrived in Vinegarroon, Texas, a rough railroad camp near the Pecos River, where lawlessness was rampant. With the nearest court 200 miles away in Fort Stockton, the Texas Rangers needed a local authority to maintain order. On August 2, 1882, Bean was appointed Justice of the Peace for Pecos County and also served as a notary public. He soon moved to Langtry, where he established the Jersey Lilly saloon, named after the British actress Lillie Langtry, whom he admired from afar. Above the saloon’s entrance, a sign proudly declared: “Judge Roy Bean, Notary Public, Justice of the Peace, Law West of the Pecos.”

Bean’s notary office was not a separate entity but part of the saloon, where he conducted legal duties alongside serving whiskey. As a notary, he authenticated documents, performed marriages, and granted divorces (often illegally, for a fee of $10). His equipment was minimal: a single law book (the 1879 Revised Statutes of Texas), a .41 Smith & Wesson revolver used as a gavel, and his notary public seal, which survives today at the Judge Roy Bean Visitor Center.

A Unique Approach to Justice

Bean’s notary office was as unconventional as his courtroom. His rulings were often arbitrary, guided by pragmatism rather than strict legal precedent. For instance, he once fined a corpse $40 for carrying a concealed weapon, using the money to cover burial costs. In another case, he dismissed a charge against an Irishman for killing a Chinese laborer, claiming he found no law against “killing a Chinaman.” Such decisions, while questionable, were final, as there was no higher court to appeal to in the remote region.

Despite his reputation as a “hanging judge,” Bean sentenced only two men to death, one of whom escaped. His leniency toward horse thieves, often releasing them if the horses were returned, contrasted with harsher jurisdictions. Bean’s notary work, including certifying documents and performing marriages, was practical for a frontier community lacking formal institutions, but he often pocketed fines and fees to supplement his saloon income.

The Jersey Lilly and Cultural Legacy

The Jersey Lilly saloon, housing Bean’s notary office and courtroom, was a hub of activity. Bean adorned it with signs advertising “Ice Cold Beer” and a faded poster of Lillie Langtry, whom he claimed the town was named after (though it was actually named for railroad engineer George Langtry). His infatuation with the actress led him to build an adobe “Opera House” in her honor, hoping she would visit. In 1890, he even flagged down a train carrying railroad magnate Jay Gould, inviting him to the saloon under the pretense of a bridge emergency, showcasing his flair for self-promotion.

Bean’s eccentricities made him a folk hero. His notary office, though rudimentary, symbolized order in a lawless region. After his death in 1903 from lung and heart ailments, the Texas Highway Department acquired the Jersey Lilly in 1936, restoring it as a historic site. Today, the Judge Roy Bean Visitor Center in Langtry preserves artifacts like his notary seal, law book, and handcuffs, offering a glimpse into his life through dioramas and a cactus garden.

Impact and Myth

Bean’s notary office, inseparable from his saloon and courtroom, was a product of the Wild West’s rough-and-tumble environment. While myths portray him as a ruthless “hanging judge,” historians like Jack Skiles argue he never hanged anyone, and his decisions, though unorthodox, brought stability to a chaotic frontier. U.S. District Court Judge T.A. Falvey praised Bean in 1914, stating, “He filled a place that could not have been filled by any other man.”

Bean’s legacy endures in popular culture, from films like The Westerner (1940) and The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (1972) to TV series and books. His notary office, though modest, was central to his role as a frontier arbiter, blending law, commerce, and showmanship in a way that cemented his place in American folklore. Visiting Langtry today, one can still feel the gritty spirit of the Old West, where Roy Bean’s notary public seal and six-shooter gavel defined justice west of the Pecos.

Phantly Roy Bean Jr. (c. 1825–March 16, 1903), a colorful figure of the American Old West, is best known as the self-proclaimed "Law West of the Pecos." Operating out of his saloon, the Jersey Lilly, in Langtry, Texas, Bean served as a Justice of the Peace and notary public, dispensing a unique brand of frontier justice in the desolate Chihuahuan Desert along the Rio Grande. His notary office, intertwined with his saloon and courtroom, became legendary for its eccentric rulings and Bean's larger-than-life persona.

The Origins of Bean's Notary Office

In 1882, Roy Bean arrived in Vinegarroon, Texas, a rough railroad camp near the Pecos River, where lawlessness was rampant. With the nearest court 200 miles away in Fort Stockton, the Texas Rangers needed a local authority to maintain order. On August 2, 1882, Bean was appointed Justice of the Peace for Pecos County and also served as a notary public. He soon moved to Langtry, where he established the Jersey Lilly saloon, named after the British actress Lillie Langtry, whom he admired from afar. Above the saloon’s entrance, a sign proudly declared: “Judge Roy Bean, Notary Public, Justice of the Peace, Law West of the Pecos.”

Bean’s notary office was not a separate entity but part of the saloon, where he conducted legal duties alongside serving whiskey. As a notary, he authenticated documents, performed marriages, and granted divorces (often illegally, for a fee of $10). His equipment was minimal: a single law book (the 1879 Revised Statutes of Texas), a .41 Smith & Wesson revolver used as a gavel, and his notary public seal, which survives today at the Judge Roy Bean Visitor Center.

A Unique Approach to Justice

Bean’s notary office was as unconventional as his courtroom. His rulings were often arbitrary, guided by pragmatism rather than strict legal precedent. For instance, he once fined a corpse $40 for carrying a concealed weapon, using the money to cover burial costs. In another case, he dismissed a charge against an Irishman for killing a Chinese laborer, claiming he found no law against “killing a Chinaman.” Such decisions, while questionable, were final, as there was no higher court to appeal to in the remote region.

Despite his reputation as a “hanging judge,” Bean sentenced only two men to death, one of whom escaped. His leniency toward horse thieves, often releasing them if the horses were returned, contrasted with harsher jurisdictions. Bean’s notary work, including certifying documents and performing marriages, was practical for a frontier community lacking formal institutions, but he often pocketed fines and fees to supplement his saloon income.

The Jersey Lilly and Cultural Legacy

The Jersey Lilly saloon, housing Bean’s notary office and courtroom, was a hub of activity. Bean adorned it with signs advertising “Ice Cold Beer” and a faded poster of Lillie Langtry, whom he claimed the town was named after (though it was actually named for railroad engineer George Langtry). His infatuation with the actress led him to build an adobe “Opera House” in her honor, hoping she would visit. In 1890, he even flagged down a train carrying railroad magnate Jay Gould, inviting him to the saloon under the pretense of a bridge emergency, showcasing his flair for self-promotion.

Bean’s eccentricities made him a folk hero. His notary office, though rudimentary, symbolized order in a lawless region. After his death in 1903 from lung and heart ailments, the Texas Highway Department acquired the Jersey Lilly in 1936, restoring it as a historic site. Today, the Judge Roy Bean Visitor Center in Langtry preserves artifacts like his notary seal, law book, and handcuffs, offering a glimpse into his life through dioramas and a cactus garden.

Impact and Myth

Bean’s notary office, inseparable from his saloon and courtroom, was a product of the Wild West’s rough-and-tumble environment. While myths portray him as a ruthless “hanging judge,” historians like Jack Skiles argue he never hanged anyone, and his decisions, though unorthodox, brought stability to a chaotic frontier. U.S. District Court Judge T.A. Falvey praised Bean in 1914, stating, “He filled a place that could not have been filled by any other man.”

Bean’s legacy endures in popular culture, from films like The Westerner (1940) and The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (1972) to TV series and books. His notary office, though modest, was central to his role as a frontier arbiter, blending law, commerce, and showmanship in a way that cemented his place in American folklore. Visiting Langtry today, one can still feel the gritty spirit of the Old West, where Roy Bean’s notary public seal and six-shooter gavel defined justice west of the Pecos.

Contributed by OldPik on September 3, 2024

Image

You must be logged in to comment on the photos.

Log in

Log in

No comment yet, be the first to comment...